DEFINITION OF RADICAL/PRIMITIVE VS PHONETIC:

Chinese characters and languages are actually based predominantly of Monosyllabic Words or Morphemes. These monosyllables are then combined into Polysyllabic characters or words – predominantly 2 syllables, then 3, then 4 – possibly up to 6 – but decreasing in frequency as you go along. Most new words or characters are then “produced” in modern Chinese. The notion of Radicals and Phonetics are actually based on Western Scholars’ classification of the Chinese language – as the Eastern/Chinese Classification is too cumbersome and complicated for Western Scholars – although classification by Radicals is one of 4 criteria used by Chinese Scholars..

The first part of the new word/character is called the radical and the second part is called the phonetic. The radical – or primitive as it is also referred to – gives you an idea of what the word represents and the phonetic gives you a clue as to how it is supposed to sound. Any morpheme can be a radical and any morpheme can essentially be a phonetic. All morphemes are made of certain strokes which are the basic forms of the “alphabet” – Chinese character to be written.

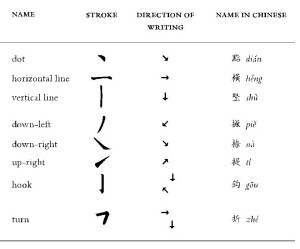

There are essentially 8 major strokes.

Table 3.1. the eight Major stroke types

Far from being complicated drawings, Chinese characters are made out of simple single strokes, all of them variations of only eight basic ones. All strokes have their own name and are written according to a few rules. It’s very important to learn to recognize them, since the number of strokes in a character is often the easiest way to find it in an index… but this will become clear after learning radicals and the use of dictionaries.

1. The following are the first six strokes, the fundamental ones:

|

heng | horizontal stroke (written from left to right) |

as in the character yi (one) |

|

shu | vertical stroke (written from top to bottom) |

as in the character shi (ten) |

|

pie | down stroke to the left (written from top right to bottom left) |

as in the character ba (eight) |

|

na | down stroke to the right (written from top left to bottom right) |

as in the character ru (to enter) |

|

dian | dot (written from top to bottom right or left) |

as in the character liu (six) |

|

ti | upward stroke (written from bottom left to top right) |

as in the character ba (to grasp) |

2. The last two strokes have several different variations. The first group is composed by five strokes with a hook:

|

henggou | horizontal stroke with a hook | as in the character zi (character) |

|

shugou | vertical stroke with a hook | as in the character xiao (small) |

|

wangou | bending stroke with a hook | as in the character gou (dog) |

|

xiegou | slant stroke with a hook | as in the character wo (I, me) |

|

pinggou | level bending stroke with a hook | as in the character wang (to forget) |

3. And the following by two single strokes with a turn:

|

shuzhe | vertical stroke with a horizontal turn to the right | as in the character yi (doctor, medicine) |

|

hengzhe | horizontal stroke with a vertical turn | as in the character kou (mouth) |

4. Combined strokes are made out of basic ones. The following are a few examples:

|

shuwangou | vertical stroke combined with a level bending stroke with a hook | as in the character ye (also) |

|

piedian | down stroke to the left combined with a dot | as in the character nu (woman) |

|

shuzhezhegou | vertical stroke with a double turn and a hook | as in the character ma (horse) |

If a character can be compared to a word in alphabetic languages, then strokes are like letters… learning them is the key to memorize characters. And then, characters don’t only need to be correct, they should also be as beautiful and balanced as possible. It is therefore necessary to copy the single strokes many times (be it with a brush or, much easier, with a pen) to memorize their shape and thickness.

http://www.clearchinese.com/chinese-writing/strokes.htm

STROKE ORDER:

Strokes are combined together according to a few fixed rules (and to several exceptions!). Learn these rules, because they’re of great help for memorizing characters. They are also fundamental in case you need to recognize the first stroke of a character, but we’ll talk about that again.

1. Strokes at the top before those at the bottom.

| The character |  san (three) |

is written this way: |  |

| The character |  tian (heaven) |

is written this way: |  |

2. Strokes to the left before those to the right.

| The character |  men (door) |

is written this way: |  |

| The character |  hua (to change) |

is written this way: |  |

3. Containing strokes before contained ones.

| The character |  si (four) |

is written this way: |  |

The sealing horizontal stroke must be written last (“close the door after you have entered the room”) |

| The character |  yue (moon) |

is written this way: |  |

But:

- When there aren’t enclosing strokes at the top of the character, enclosed strokes are written first:

The character

zhe (this)is written this way:

4. Vertical stroke in the middle before those on both sides or at the bottom.

| The character |  shui (water) |

is written this way: |  |

| The character |  shan (mountain) |

is written this way: |  |

But:

- If it crosses other strokes the vertical stroke in the middle should be written last:

The character

zhong (middle)is written this way:

The fundamental rules – from top to bottom and from left to right – are easily understandable, since they are used in Western writings, too. The others on the contrary need a few exercise. Be sure to learn from the beginning the correct way each different character should be written; otherwise you may find yourself repeating the same mistakes over and over without realizing it, especially when you’ll know hundreds of characters.

http://www.clearchinese.com/chinese-writing/stroke-order.htm

The “meaning” radicals total 52. As a matter of fact, the complete list of Chinese radicals are more than that. But I only list the ones that I perceive have the value to be memorized and eventually help you learn new characters with less effort.

(A little explanation of “meaning radicals” here: when I say “meaning radical”, it means these radicals only imply the meaning of the character. They have ZERO connection to the pronunciation of the characters.)

It is possible that I might have missed certain “meaning radical ” that worth to be included in the list. By all means, if you find one, let me know. I do appreciate.

So here we go, all the 52 “meaning radicals” in one table.

I’d strongly suggest you to memorize all of them. What you need to memorize? Their shape and meaning, that’s all. It’ll be better if you can write them down on paper while memorizing them. Some readers are using sketching pad to practice online – also a brilliant idea! If you have an iPad, android, or any other touch screen tablet or phone, you can also practice directly with your finger. After all, the goal here is to get familiar with them, the more the better.

COMPOUND WORDS

Once you have learnt the 214 or so radicals, you should realize that new words are made up by “compounding” the radicals and essentially more often – the “meaning radicals”

Here’s a breakdown, as per Mandarin Segments:

The word 存取 (cúnqǔ) can be calculated as follows: access=exist+take. Think of it like “take something that exists” – it makes up a logical build-up, like 1+2=3. Simple. This logic can be seen in many other two-character words, including:

你好 (nǐhǎo): hello = you are good

满意 (mǎnyì): satisfied = full thinking

意外 (yìwài): accident = outside your thoughts

过奖 (guòjiǎng): flatter = pass the reward

怕痒 (pàyǎng): fear the itch = ticklish

When 1+1=1

This one is mathematically slightly less intuitive, but in Chinese it makes total sense. 允许 (yǔnxǔ) is ‘permit’, and in simple terms: ‘permit’=permit+permit (允+许=允许). Good, for once Chinese seems simple. Mathematically, this can be written as 1+1=1 🙂 This is a common enough construct, and you can also see it in words like:

讨论 (tǎolùn): discuss = discuss+discuss

练习 (liànxí): practise = practise+practise

自己 (zìjǐ): self = self+self

选择 (xuǎnzé): choose = choose+choose

依赖 (yīlài): reply = rely+rely

应该 (yīnggāi): should = should+should

休息 (xiūxi): rest = rest+rest

帮助 (bāngzhù): help = help+help

号码 (hàomǎ): number = number+number

(And so many others: 犯罪, 错误, 继续, …)But, we can also observe some others in use …

When -1+1=0

This is well-known way of creating words in Mandarin, and there are plenty of blog posts where people have written about this. Some of the better known examples include:

多少 (duōshao): lots+little = how much

左右 (zuǒyòu): left+right = approximately

上下 (shàngxià): up+down = about

大小 (dàxiǎo): big+small = size

东西 (dōngxi): east+west = things

买卖 (mǎimài): buy+sell = business

When 1+2=12

楼下 (lóuxià): building+down = downstairs

水平 (shuǐpíng): water+level = horizontal

领带 (lǐngdài): neck+strap = necktie

声频 (shēngpín): sound+frequency = audio frequency

(And I’m sure you can derive many more instances of this type yourself!)

When 1-1=1

Yes, this exists too – where even introducing a completely contradictory word doesn’t change the meaning of the first …

忘记 (wàngjì): forget+remember = forget

全部 (quánbù): whole+part = whole

但是 (dànshì): but+indeed = but

毒药 (dúyào): poison+medicine = poison

When 376+1=1

白痴 (báichī): white(!)+dumb = dumb

干净 (gānjìng): dry(!)+clean = clean

原谅 (yuánliàng): source(!)+forgive = forgive

愉快 (yúkuài): pleasant+fast(!) = pleasant

When 1+2=634

How about this …

漂亮 (piàoliang): pretty = tossed light

面包 (miànbāo): surface+package = bread

马上 (mǎshàng): horse+on = immediately

有机 (yǒujī): have+machine = organic

厉害 (lìhai): severe+injury = awesome

消息 (xiāoxi): extinguish+rest = news