Analyses of characters since ancient times have indicated several major methods by which characters were formed.

This work was first done in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) by a philologist named Xuˇ Shèn 許慎 in a book titled Shuō wén jiě zì 說文解字, or Analysis of Characters. Xu Shen divided all characters used in his day into two broad categories: single-component characters (such as 木 mù, “tree”) and multiple-component characters (such as 林 lín, “woods,” which combines two “tree” symbols into one character). Single-component characters are called 文 wén and multiple-compo- nent characters 字 zì. Hence, the literal translation of the title of Xu Shen’s book is “speaking of wen and explanation of zi.” Six categories of characters were identified that ref lect major principles of character formation and use. The book lists 9,353 characters plus 1,163 variant forms. It is believed to be the most comprehensive study of characters in use during that time.

Within Xu Shen’s six classes, four (classes 1, 2, 3, and 5) have to do with the for- mation of characters. The other two regard character use. The sixth class, known as 轉注 zhuanzhù or “semantic transfer,” will not be looked at in detail here be- cause it involves disagreement among scholars, and examples are scarce. For people without knowledge of Chinese writing, the etymology of the examples for each category is quite interesting. They make useful mnemonic devices for learning some characters.

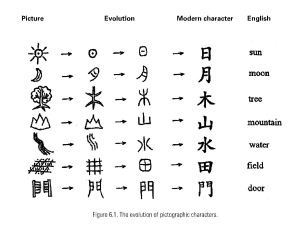

PICTOGRAPHS

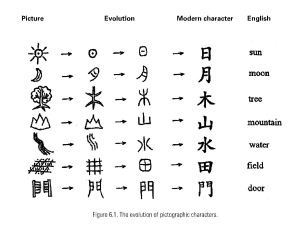

Many early written signs in Chinese originated from sketches of objects. Thus they bore a physical resemblance to the objects they represented, like pictures, which is why they are called pictographs. Gradually they evolved from the original pictographic symbols into their modern forms by a process of simplification and abstraction, during which details were left out and curves were changed into straight lines. As a result, modern characters are far removed from their original pictures, al- though they sometimes still show traces of the objects they represent. Although these are the most frequently used examples of pictographic characters, modern people without any knowledge of Chinese characters, when seeing these sym- bols, would make no connection to their referents before the similarities were explained. The character 日 rì, “sun,” for example, looks more like a window, while the character 月 yuè, “moon,” resembles a stepladder. Generally speaking, without knowing the meaning of these characters, one cannot decode them by merely looking.

INDICATIVES

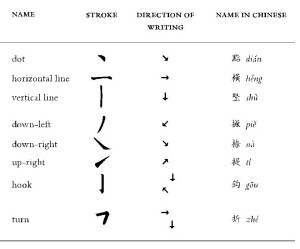

An indicative is a character made by adding strokes to another symbol in order to indicate the new character’s meaning. For example,

刃 rèn, “blade.” A dot is added to 刀 dāo, “knife.”

旦 dàn, “morning.” A horizontal line is added underneath 日 rì, “sun” to show the time when the sun is just above the horizon.

本 běn, “root.” A short line is added to 木 mù, “tree.”

SEMANTIC COMPOUNDS

Semantic compounds are constructed by combining two or more components that collectively contribute to the meaning of the new character. Examples are

明 míng, “bright,” is a combination of 日 rì, “sun,” and 月 yuè, “moon.”

信 xìn, “trust,” combines 人 rén, “person,” and 言 yán, “words.”

看 kàn, “look,” has 手 shoˇu, “hand,” over 目 mù, “eye.”

林 lín, “woods,” shows two 木 mù, “tree.”

森 sēn, “forest,” is composed of three 木 mù, “tree.”

囚 qiú, “prison,” is represented by a 人 rén, “person,” in 囗, confinement.

BORROWING

Borrowing in this context refers to the use of existing characters to represent additional new meanings. Two frequently used examples are

來 lái, originally a pictograph for “wheat.” The written character with its pronunciation was later borrowed to mean “to come.” In time, the borrowed meaning prevailed, and the original meaning of “wheat” died away.

去 qù, originally a pictograph for a cooking utensil. Later the character was borrowed to mean “to go.” The borrowed mean- ing also prevailed, and the original meaning died away.

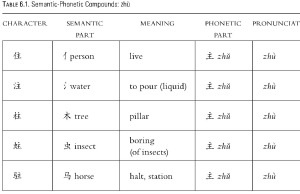

SEMANTIC PHONETIC

Semantic-phonetic compounds are a hybrid category constructed by combining a meaning element and a sound element. This method of character formation thrived as a means to solve the ambiguity problem caused by borrowing. As can be easily seen, when a particular character is borrowed to mean more and more different things, sooner or later, the interpretation of the multiple-meaning writ- ten sign becomes a problem. To solve the problem and to allow borrowing to continue, a semantic element is added to indicate the specific meaning of the new character. This process led to the creation of semantic-phonetic compounds.

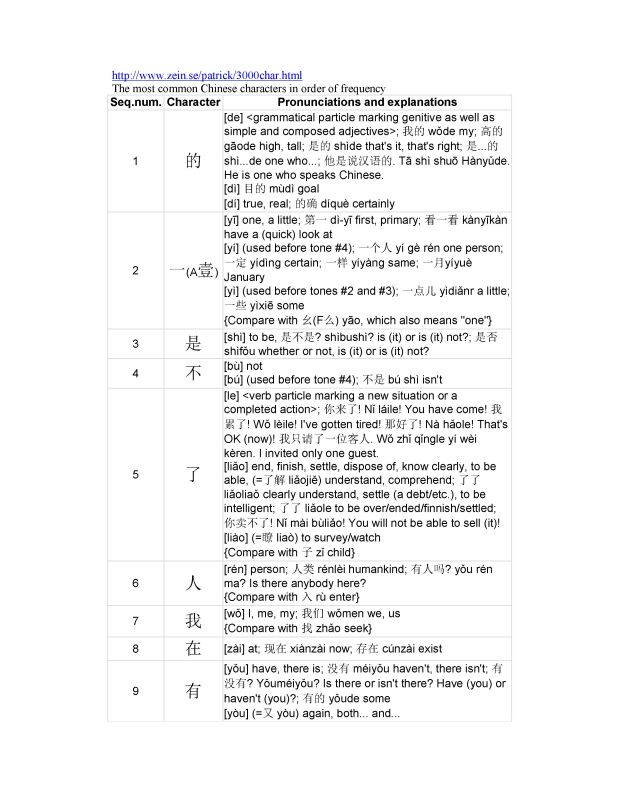

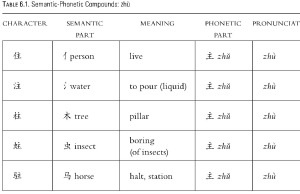

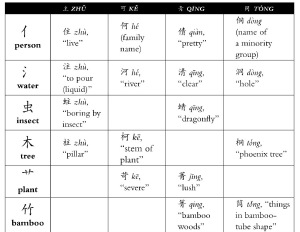

Thus, a semantic-phonetic compound has two components, one indicating meaning and the other pronunciation. Take 主 zhuˇ, “host,” as an example. In modern Chinese, the character is used as a phonetic element in more than ten semantic-phonetic compounds, five of which are shown in Table 6.1. The five characters in the first column are pronounced exactly the same way, zhù, although they are different in meaning. They share the same phonetic element, 主 zhuˇ, which is the right-hand side of the characters. The signs on the left are semantic components, which offer some clue to the meaning of the characters.

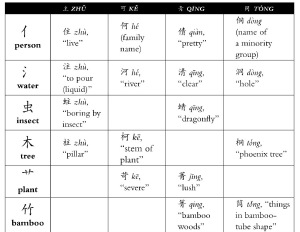

The semantic elements, for example, 亻, “person,” 氵, “water,” and 木, “tree,” are pictographs commonly known as “radicals.” Their function is to hint at the meaning of the characters in which they appear. At the same time, they also group semantically related characters into classes. For example, all the characters with 亻, “person,” as a component have to do, at least in theory, with a person or people; all the characters with 木, “tree,” as a component have to do with wood or trees. Traditionally, Chinese characters are categorized under 214 radicals. One way to organize characters in dictionaries is to group them under these radicals.

Table 6.2 brief ly illustrates the combination of semantic and phonetic elements in the formation of characters. The vertical columns group characters by phonetic elements, and the horizontal rows group characters by semantic elements. In other words, characters in the same column have phonetic similarities and those in the same row share semantic features. As seen in Table 6.2, the arrangement of the two elements in a semantic-phonetic compound can be left to right or top to bottom (as in 菁, 筒, and 苛). Other patterns not shown here include outside to inside, as in the character 国 guó, “country.” Radicals may take any position in a character.

In modern Chinese, the majority of characters in the writing system belong to the category of semantic-phonetic compounds. From as early as the Han dynasty, this became the most productive method for creating new characters. It is worth noting, however, that there are problems with extensive reliance on semantic- phonetic characters. Languages change over time, and Chinese is no exception. Both the pronunciation and the meaning of characters are in a state of f lux. While the written signs remain constant, over time sound change and semantic evolution have eroded the relationships between characters and their sound and semantic components, making it more and more difficult to deduce the meaning and pronunciation of a character from its written form. Now, as can be partially seen in Table 6.2, phonetic elements do not indicate the pronunciation of the characters

clearly and accurately; nor do semantic elements show the exact meaning of char- acters. In modern Chinese, the value of semantic-phonetic characters resides in the combination of these two types of information to determine a character’s meaning and pronunciation.

The third stage combines semantic and phonetic information to create new characters. This is the highest stage of development, completed in the Han dynas- ty, about two thousand years ago, when the Chinese writing system reached maturity. No new method has appeared since then, although the existing categories of characters have grown and shrunk. In modern Chinese, more than 90 percent of characters in use are semantic-phonetic compounds; those that can be traced back to their pictographic origins comprise less than 3 percent.

SCRIPTS AND STYLES

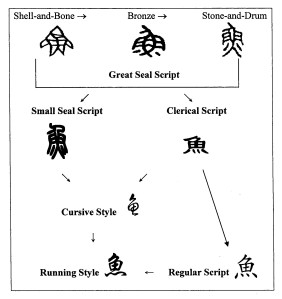

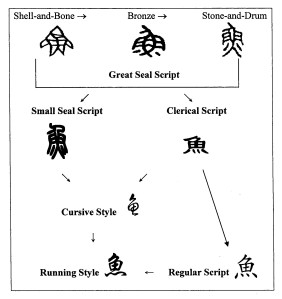

Strictly speaking, only four scripts played major roles in the development of the Chinese writing system: Great Seal (大篆 dàzhuàn), Small Seal (小篆 xiaozhuàn), Clerical (隸書 lìshū), and Regular (楷書 kaishū). They are considered major scripts because at different times they were formally adopted for official documentation. Great Seal Script is a cover term for several ancient scripts used over 1,200 years before the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), including Shell and Bone Script (甲骨文 jiaguwén), Bronze Script (金文 jīnwén), and Stone Drum Script (石鼓文 shíguˇwén).3 Since the Qin dynasty, three major script changes have taken place: from Great Seal to Small Seal, from Small Seal to Clerical, and from Clerical to Regular.

The Running (行書 xíngshū) and Cursive styles (草書 caoshū) were initially developed as informal ways to increase writing speed. Later they were also adopted for art. However, they do not represent major script changes; they only reflect modifications of the major scripts. As will be discussed below, they are much less standardized and are not used in official documents. For that reason, they are referred to as styles rather than scripts.

Ref: CHINESE WRITING AND CALLIGRAPHY – WENDAN LI