As emphasized at the beginning, this site is to help those with some basic knowledge of Hakka, Cantonese and Mandarin without formal Writing and Mandarin skills, to upgrade their knowledge to be proficient in an increasingly important Chinese Official Language, that is used by almost 1 in 5 inhabitants of Earth.

This is NOT a Didactic Collection of Lectures, but more a Do-It-Yourself Manual/Resource.

It is a Collection of Data and Resources to help Accelerate and Formalize a Teaching and Learning method peculiar to your specific needs and goals.

Here is a REPEAT TUTORIAL on its actual IMPLEMENTATION.

First of ALL, THERE IS NO WAY TO BYPASS THE MEMORIZATION OF SPECIFIC BASICS – ESPECIALLY TONE, BUT IF WE SET OFF WITH THE PREMISE THAT THERE IS ALREADY SOME SPOKEN BACKGROUND IN HAKKA OR CANTONESE, THIS ASPECT HAS ALREADY BEEN ADDRESSED AND ITS MORE A PROCESS OF UTILIZATION TO GET THE PERFECT TONES – 7 -9 in Hakka, at least 7 in Cantonese and only 4 in Mandarin.

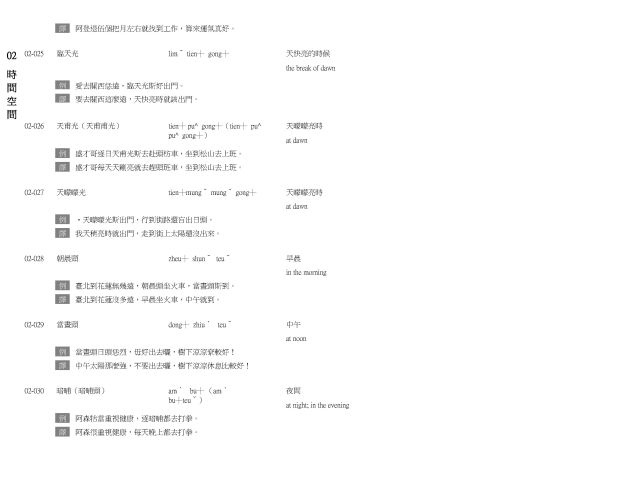

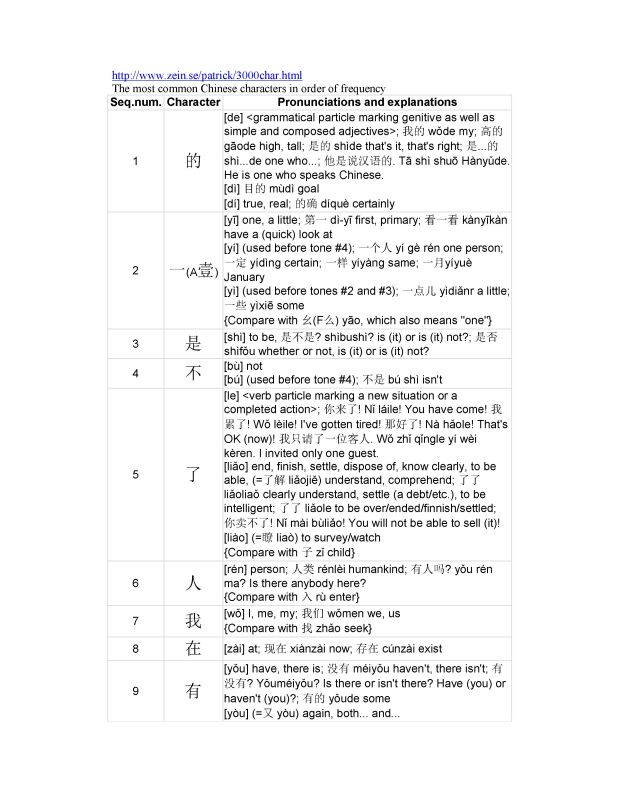

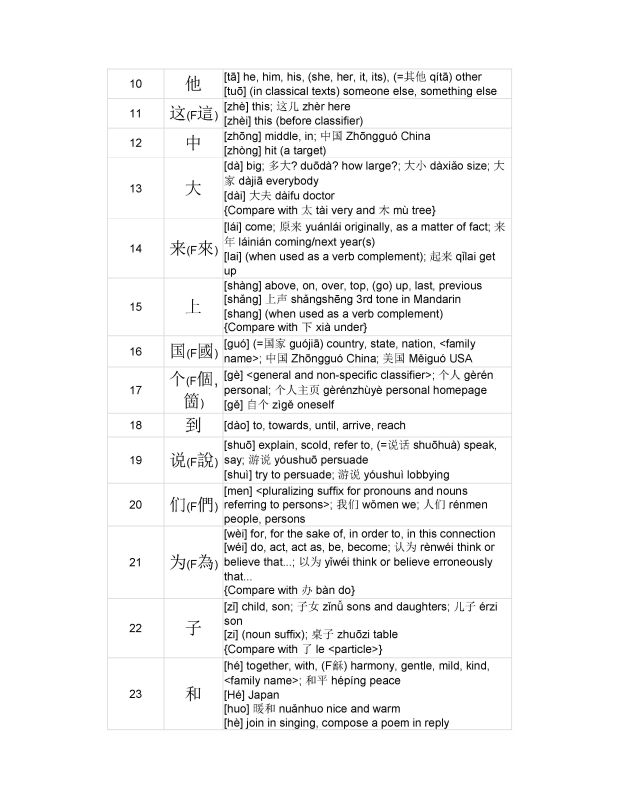

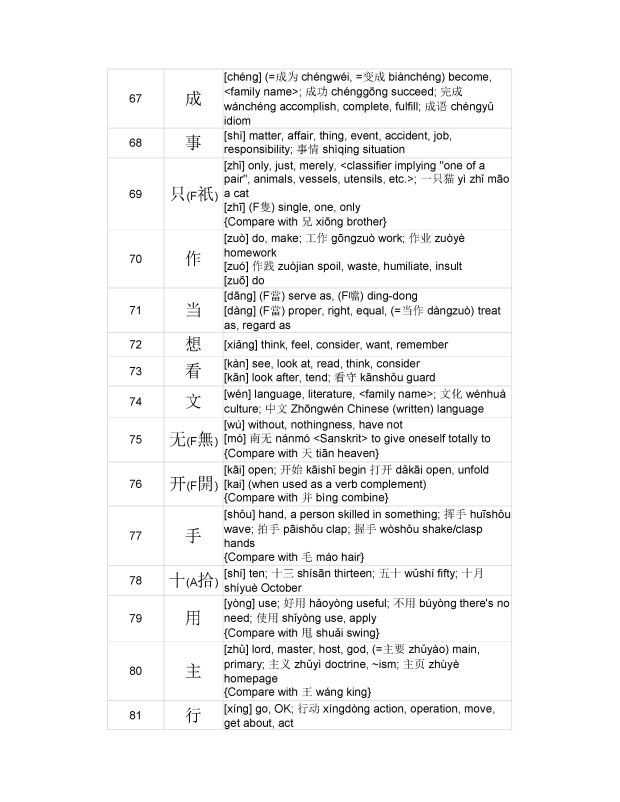

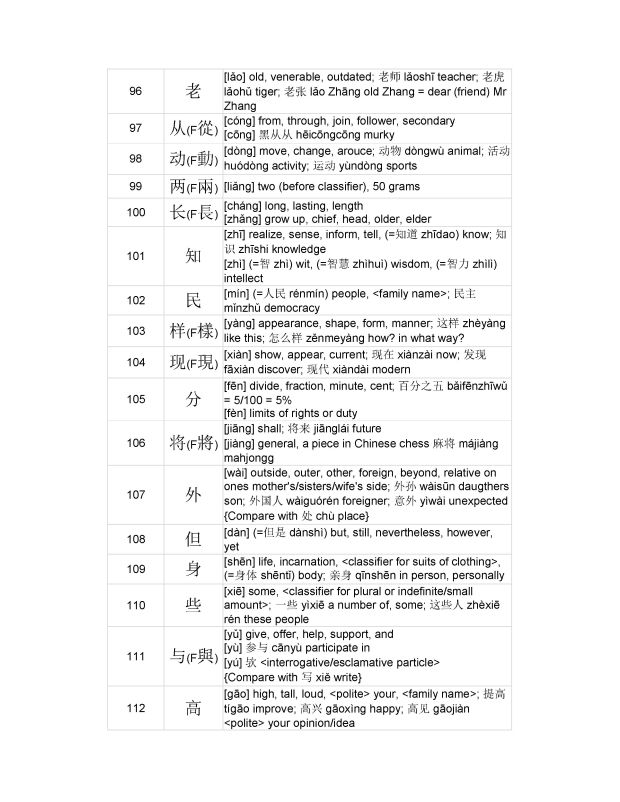

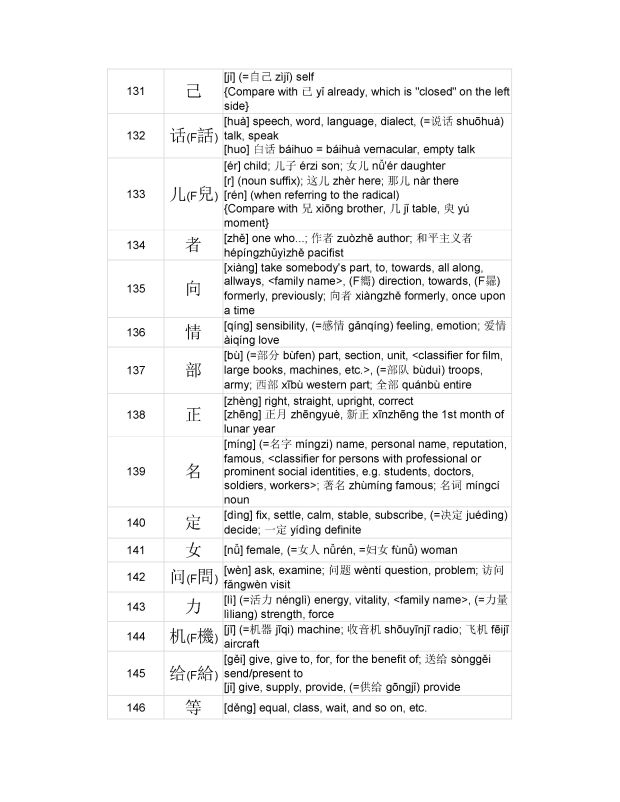

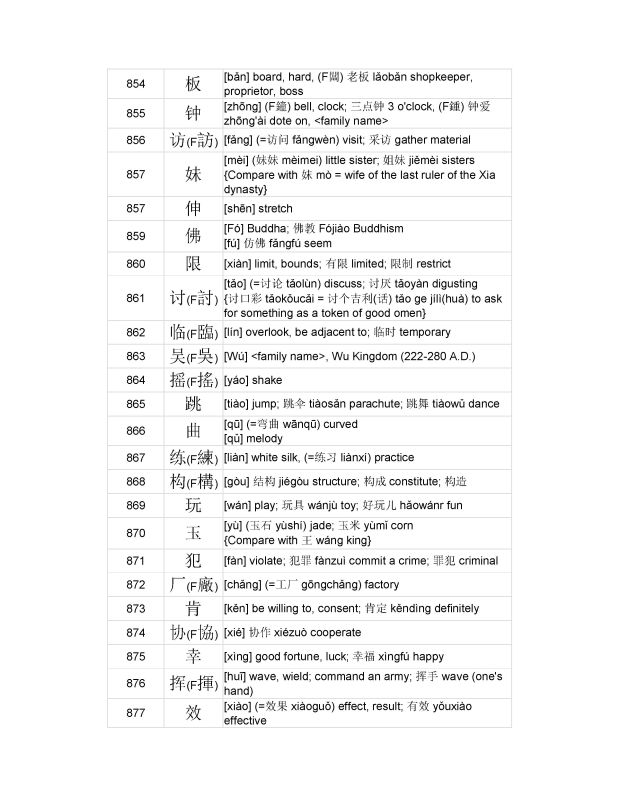

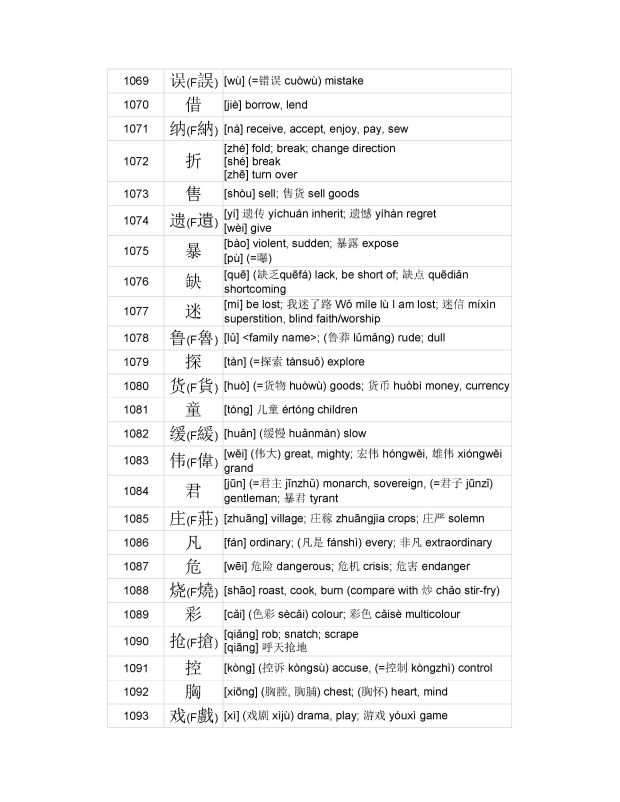

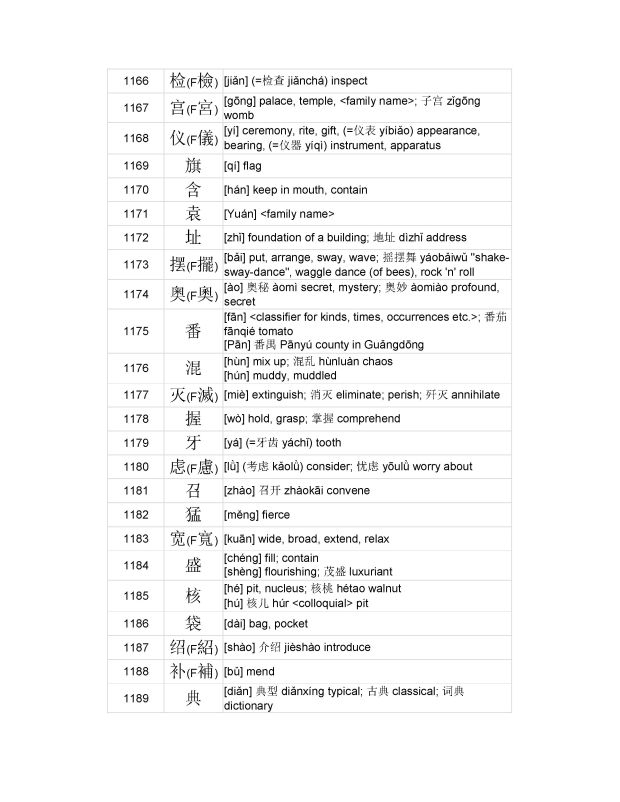

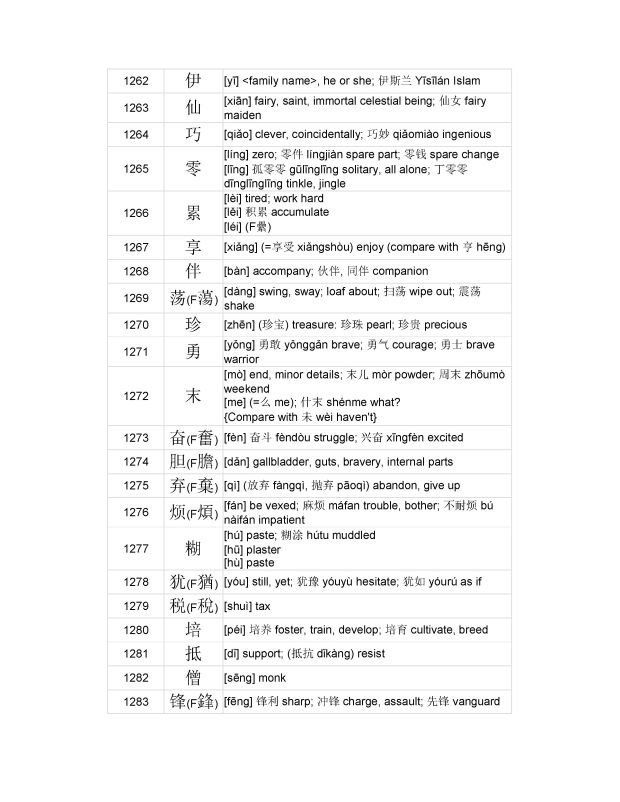

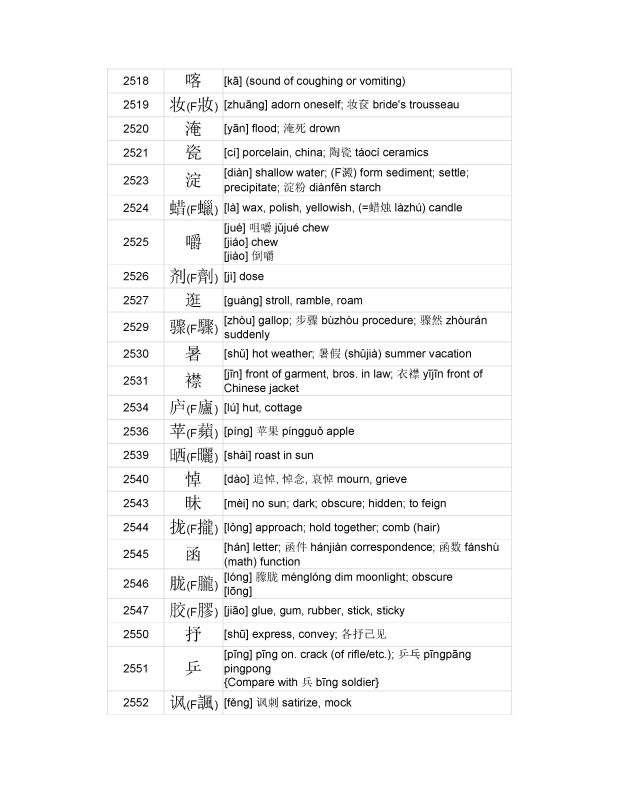

Memorizing the Chinese Characters can be accomplished by Referring to the 214 Generally accepted Radicals, deciding whether to learn SIMPLIFIED (Mainland Chinese) or TRADITIONAL (Non-Mainland Chinese – including Taiwan) Chinese characters. This can be simplified down to the ESSENTIAL 54 RADICALS – the ones statistically found to be used the most often and by various memorization techniques e.g. FLASHCARDS, MNEMONICS OR STORY-LINES – as popularized by the HEISIG METHOD.

Then, it boils down to putting things into practice, hence this tutorial.

Let us take the English word for clothing. These r just illustrations of programs mentioned in this blog and can be interchanged for any program that works best for your circumstances.

CLOTHING:

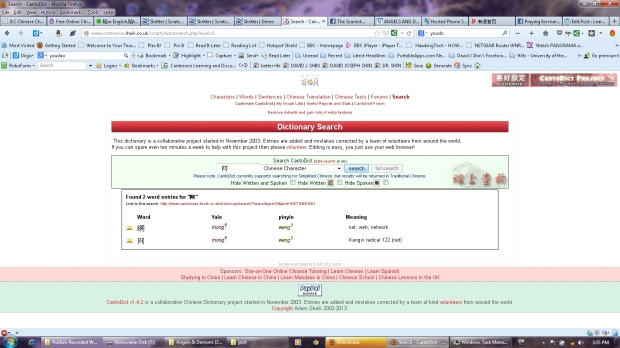

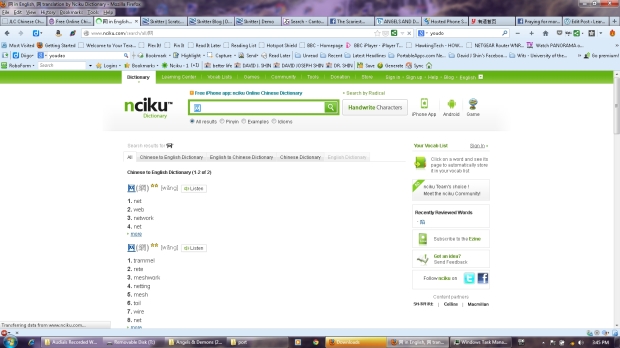

First look up the Chinese Character. I find the programs based on the Cantodict Databases or CC-CEDIT Databases the most useful personally, especially the ones accepting English, Handwritten, Voice, and even OCR. My favorite in NCIKU:

LET US CHOOSE ZHUANG (by clicking on “more” below the word after the character):

NOW CLICK ON “STROKE ORDER”:

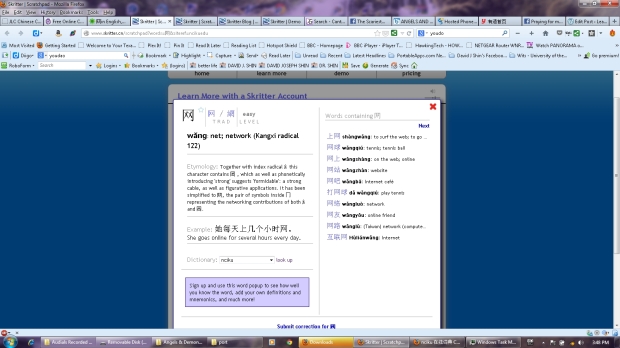

Unfortunately the Adobe Flash portion is not captured. BUT, MORE IMPORTANTLY, CLICK ON THE “PRACTICE WRITING ON SKRITTER” LINK.

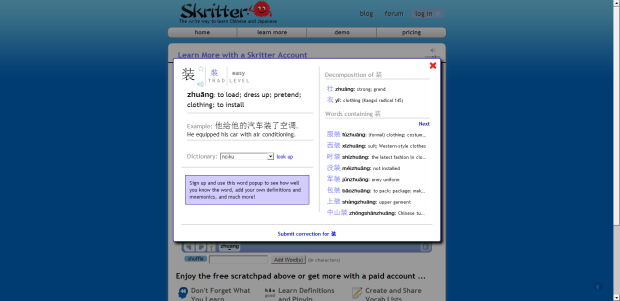

Again, apologies for the non screen-capture of the Adobe Flash components. NOW CLICK ON THE MAGNIFYING GLASS ICON ON THE EXTREME RIGHT:

THEN – LOOK UP THE INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERS, OR EXPLORE WORDS THAT CONTAIN THE SAME CHARACTERS, ETC. NOTICE THE NEXT BUTTONS AT THE TOP RIGHT OF THE NEW FRAMES THAT POP UP THAT GIVES U MORE RESULTS. ONE WORD OPENS UP A MYRIAD OF NEW WORDS. FADSCINATING AT THE LEAST – ESPECIALLY AS FAR AS ETYMOLOGY IS CONCERNED.

NOTICE, ON THE MAIN PANEL/FRAME – THERE IS A “DICTIONARY LOOK-UP” BUTTON, WHICH IS PREPOPULATED WITH NCIKU, AS THIS WAS THE SITE REFERRING U TO SKRITTER. IF U CLICK ON THIS – IT TAKES U BACK TO THE NCIKU SITE. BUT, MORE IMPORTANTLY – IF U HAVE A REGISTERED NCIKU ACCOUNT – IT SAVES THE CHARACTERS INTO YOUR WORD-LIST”. There is NO CHARGE for an NCIKU Account (but a donation is encouraged) or to use SKRITTER thru NCIKU – Skritter is an Excellent resource and is otherwise about $20/month to use. A NCIKU Account allows u to also print out free FLASH CARDS and is almost a complete ANKI Alternative.

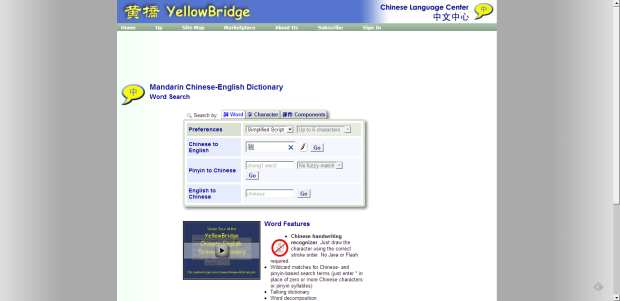

FINALLY, if u want to see the other Dialects, especially Cantonese, or even Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese, character and do a search on Yellowbridge, which opens up more explanations and links:

Click on the VARIOUS FOLDERS AT THE TOP LEFT:

WALLA, Cantonese – Jtutping and Yale, (together with Japanese and Korean).