A list of Hakka phrases.

THE HAKKA LANGUAGE

Hakka is one of the major minority Han dialects of China. After Mandarin, comes Cantonese, Gan (of which Hakka has at times been classified as a subdivision), Min, Hakka and then the other less well known dialects.

According to published articles (Alternopedia – direct quotes):

Hakka Chinese

| Hakka | |

|---|---|

| 客家話 / 客家话 | |

|

Hak-kâ-fa/Hak-kâ-va (Hakka/Kejia) written in Chinese characters |

|

| Native to | Mainland China, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan,Japan (due to presence of Taiwanese community in Tokyo-Yokohama Metropolitan Area), Singapore, Philippines,Indonesia, Mauritius, Suriname, South Africa, India and other countries where Hakka Chinese migrants have settled. |

| Region | in China: Eastern Guangdong province; adjoining regions of Fujian and Jiangxiprovinces |

| Ethnicity | Hakka people (Han Chinese) |

| Native speakers | 31 million (2007)[1] |

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan |

| Writing system | hanzi, romanization[2] |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | none (legislative bills have been proposed for it to be one of the ‘national languages’ in the Republic of China); one of the statutory languages for public transport announcements in the ROC [2]; ROC government sponsors Hakka-language television station to preserve language |

| Regulated by | The Guangdong Provincial Education Department created an official romanisation of Meixian Hakka dialect in 1960, one of four languages receiving this status in Guangdong. It is called Kejiahua Pinyin Fang’an. |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hak |

|

|

| Hakka | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 客家話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 客家话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hakka | Hak-kâ-fa or Hak-kâ-va |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hakka is one of the major Chinese language subdivisions or varieties and is spoken natively by the Hakka people in southern China, Taiwan and throughout the diasporaareas of East Asia, Southeast Asia and around the world.

Due to its primary usage in scattered isolated regions where communication is limited to the local area, the Hakka language has developed numerous variants or dialects, spoken in Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, and Guizhouprovinces, including Hainan island, Sabah, Singapore and Taiwan. Hakka is notmutually intelligible with Mandarin, Wu, Min Nan, or other branches of Chinese. It is most closely related to Gan, and is sometimes classified as a variety of Gan.[3]

Taiwan, where Hakka language is the mother tongue of a significant minority of the island’s residents, is an important world center for study of the language. Pronunciation differences exist between the Taiwanese Hakka dialect and China’s Guangdong Hakka dialect, and even in Taiwan two local varieties of Hakka exist within that dialect.

The Moi-yen/Moi-yan (梅縣, Pinyin: Méixiàn) dialect of northeast Guangdong in China has been taken as the “standard” dialect by the Chinese government. TheGuangdong Provincial Education Department created an official romanization of Moiyen in 1960, one of four languages receiving this status in Guangdong.

Contents |

Etymology

The name of the Hakka people who are the predominant original native speakers of the language literally means “guest families” or “guest people”: Hak 客 (Mandarin: kè) means “guest”, and ka 家 (Mandarin: jiā) means “family”. Amongst themselves, Hakka people variously called their language Hak-ka-fa (-va) 客家話, Hak-fa (-va), 客話, Tu-gong-dung-fa (-va) 土廣東話, literally, “Native Guangdong language,” and Ngai-fa (-va) 話, “My/our language”.

History

Early history

The Hakka people have their origins in several episodes of migration from northernChina into southern China during periods of war and civil unrest.[4] The forebears of the Hakka came from present-day Henan and Shaanxi provinces, and brought with them features of Chinese languages spoken in those areas during that time. (Since then the speech in those regions has evolved into dialects of modern Mandarin.) Hakka is quite conservative, and is generally closer to Middle Chinese than other modern Chinese languages.[5] The presence of many archaic features occur in modern Hakka, including final consonants -p -t -k, as are found in other modern southern Chinese languages, but which have been lost in Mandarin. The difference between Hakka and the better-known Cantonese may be compared to that between Portuguese and Spanish, whereas Mandarin might be compared to French – more distantly related, and with a quite different phonology.

Due to the migration of its speakers, the Hakka language may have been influenced by other language areas through which the Hakka-speaking forebears migrated. For instance, common vocabulary are found in Hakka, Min, and She (Hmong–Mien) languages.

Some people consider Hakka to have mixed with other languages, such as the language of theShe people, throughout its development.

Linguistic development

A regular pattern of sound change can generally be detected in Hakka, as in most Chinese languages, of the derivation of phonemes from earlier forms of Chinese. Some examples:

- Characters such as 武 (war, martial arts) or 屋 (room, house), pronounced roughly mwioand uk in Early Middle Chinese, have an initial v phoneme in Hakka, being vu and vuk in Hakka respectively (Mandarin: wu).

- The initial phonemes of the characters 人 and 日, among others, are a ng consonant in Hakka (人:ngin, 日:ngit), and have a corresponding reading in Mandarin as an initial r-consonant.

- The initial consonant phoneme exhibited by the character 話 (word, speech; Mandarinhua) is pronounced f or v in Hakka (v does not properly exist as a distinct unit in many Chinese languages).

- The initial consonant of 學 hɔk usually corresponds with an h [h] approximant in Hakka and a voiceless alveo-palatal fricative (x [ɕ]) in Mandarin.

Phonology

Dialects

The Hakka language has as many regional dialects as there are counties with Hakka speakers in the majority. Some of these Hakka dialects are not mutually intelligible with each other. Surrounding Meixian are the counties of Pingyuan 平遠 (Hakka: Pin Yen), Dabu 大埔 (Hakka: Tai Pu), Jiaoling 蕉嶺 (Hakka: Jiao Liang), Xingning 興寧 (Hakka: Hin Nen), Wuhua 五華 (Hakka: Ng Fah), and Fengshun 豐順 (Hakka: Foong Soon). Each is said to have its own special phonological points of interest. For instance, the Xingning does not have rimes ending in [-m] or [-p]. These have merged into [-n] and[-t] ending rimes, respectively. Further away from Meixian, the Hong Kong dialect lacks the [-u-] medial, so whereas Moiyen pronounces the character 光 as [kwɔŋ˦], Hong Kong Hakka dialect pronounces it as [kɔŋ˧], which is similar to the Hakka spoken in neighbouring Shenzhen.

As much as endings and vowels are important, the tones also vary across the dialects of Hakka. The majority of Hakka dialects have six tones. However, there are dialects which have lost all of their Ru Sheng tones, and the characters originally of this tone class are distributed across the non-Ru tones. Such a dialect is Changting 長汀 which is situated in the Western Fujian province. Moreover, there is evidence of the retention of an earlier Hakka tone system in the dialects of Haifeng 海豐 and Lufeng 陸豐 situated on coastal south eastern Guangdong province. They contain a yin-yang splitting in the Qu tone, giving rise to seven tones in all (with yin-yang registers in Ping and Ru tones and a Shang tone).

In Taiwan, there are two main dialects: Sixian (Hakka: Siyen 四縣) and Haifeng (Hakka: Hoi Foong 海豐), alternatively known as Hailu (Hakka: Hoiluk 海陸). Hakka dialect speakers found on Taiwan originated from these two regions. Sixian (Hakka: Siyen 四縣) speakers come from Jiaying 嘉應 and surrounding Jiaoling, Pingyuan, Xingning, and Wuhua. Jiaying county later changed its name to Meixian. The Hoiliuk dialect contains postalveolar consonants ([ʃ], [ʒ], [tʃ], etc.), which are uncommon in other southern Chinese languages. Wuhua, Dabu, and Xingning dialects have two sets of fricatives and affricates.

| • Huizhou (Hakka) dialect | 惠州客家話 |

| • Meizhou dialect | 梅州客家話 |

| • Wuhua dialect | 五華客家話 |

| • Xingning dialect | 興寧客家話 |

| • Pingyuan dialect | 平遠客家話 |

| • Jiaoling dialect | 蕉嶺客家話 |

| • Dabu dialect | 大埔客家話 |

| • Fengshun dialect | 豐順客家話 |

| • Longyan dialect | 龍岩客家話 |

| • Lufeng (Hakka) dialect | 陸豐客家話 |

Ethnologue reports the dialects as Yue-Tai (Meixian, Wuhua, Raoping, Taiwan Kejia: Meizhou above), Yuezhong (Central Guangdong), Huizhou, Yuebei (Northern Guangdong), Tingzhou (Min-Ke), Ning-Long (Longnan), Yugui, Tonggu.

Vocabulary

Like other southern Chinese languages, Hakka retains single syllable words from earlier stages of Chinese; thus it can differentiate a large number of working syllables by tone and rime. This reduces the need for compounding or making words of more than one syllable. However, it is also similar to other Chinese languages in having words which are made from more than one syllable.

| Hakka hanzi | Prouncation | English | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 人 | [ŋin˩] | person | |

| 碗 | [ʋɔn˧˩] | bowl | |

| 狗 | [kɛu˧˩] | dog | |

| 牛 | [ŋiu˩] | cow | |

| 屋 | [ʋuk˩] | house | |

| 嘴 | [tsɔi˥˧] | mouth | |

| 𠊎 | [ŋai˩] | me / I | In Hakka, the standard Chinese equivalent 我 is pronounced [ŋɔ˧]. |

| 渠[6] or 𠍲[7] | [ki˩] | he / she / it | In Hakka, the standard Chinese equivalent 他 / 她 / 它 is pronounced [tʰa˧]. |

| Hakka hanzi | Prouncation | English |

|---|---|---|

| 日頭 | [ŋit˩ tʰɛu˩] | sun |

| 月光 | [ŋiɛt˥ kʷɔŋ˦] | moon |

| 屋下 | [ʋuk˩ kʰa˦] | home |

| 屋家 | ||

| 電話 | [tʰiɛn˥ ʋa˥˧] | telephone |

| 學堂 | [hɔk˥ tʰɔŋ˩] | school |

Hakka prefers the verb [kɔŋ˧˩] 講 when referring to speaking rather than the Mandarin shuō 說 (Hakka [sɔt˩]).

Hakka uses [sit˥] 食, like Cantonese [sɪk˨] for the verb “to eat” and 飲 [jɐm˧˥] (Hakka [jim˧˩]) for “to drink”, unlike Mandarin which prefers chī 吃 (Hakka[kʰiɛt˩]) as “to eat” and hē 喝 (Hakka [hɔt˩]) as “to drink” where the meanings in Hakka are different, to stutter and to be thirsty respectively.

| Hanzi | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|

| 阿妹, 若姆去投墟轉來唔曾? | [a˦ mɔi˥, ɲja˦ mi˦ hi˥ tʰju˩ hi˦ tsɔn˧˩ lɔi˩ m˦ tsʰɛn˩] | Has your mother returned from going to the market yet, child? |

| 其佬弟捉到隻蛘葉來搞. | [kja˦ lau˧˩ tʰai˦ tsuk˧ tau˧˩ tsak˩ jɔŋ˩ jap˥ lɔi˩ kau˧˩] | His younger brother caught a butterfly to play with. |

| 好冷阿, 水桶个水敢凝冰阿 | [hau˧˩ laŋ˦ ɔ˦, sui˧˩ tʰuŋ˧ kai˥˧ sui˧˩ kam˦ kʰɛn˩ pɛn˦ ɔ˦] | It’s very cold, the water in the bucket has frozen over. |

Writing systems

Various dialects of Hakka have been written in a number of Latin orthographies, largely for religious purposes, since at least the mid-19th century.

Currently the single largest work in Hakka is the New Testament and Psalms (1993, 1138 pp., see The Bible in Chinese: Hakka), although that is expected to be surpassed soon by the publication of the Old Testament. These works render Hakka in both romanization (pha̍k-fa-sṳ) and Han characters (including ones unique to Hakka) and are based on the dialects of Taiwanese Hakka speakers. The work of Biblical translation is being performed by missionaries of the Presbyterian Church in Canada.

The popular The Little Prince has also been translated into Hakka (2000), specifically the Miaoli dialect of Taiwan (itself a variant of the Sixian dialect). This also was dual-script, albeit using the Tongyong Pinyin scheme.

See also

Further reading

- Mantaro J. Hashimoto (2010). The Hakka Dialect: A Linguistic Study of Its Phonology, Syntax and Lexicon. Volume 5 of Princeton/Cambridge Studies in Chinese Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 612. ISBN 0-521-13367-X.http://books.google.com/books?id=6MkgQ86JWCYC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 1st of March, 2012.

- Simon Hartwich Schaank (1897) (in Dutch). Het Loeh-foeng-dialect. BOEKHANDEL EN DRUKKERIJ VOORHEEN E. J. BRILL LEIDEN: E.J. Brill. pp. 226. http://books.google.com/books?id=VC4OAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 1st of March, 2012.

References

Footnotes

- ^ Nationalencyklopedin “Världens 100 största språk 2007” The World’s 100 Largest Languages in 2007

- ^ Hakka was written in Chinese characters by missionaries around the turn of the 20th century.[1]

- ^ Thurgood & LaPolla, 2003. The Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge.

- ^ Hakka Migration

- ^ Language

- ^ p.xxvi 客語拼音字彙, 劉鎮發, 中文大學出版社, ISBN 962-201-750-9

- ^ http://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/yitic/frc/frc00280.htm

Notations

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology – the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015831-1. http://books.google.com/?id=7BLQcXUht2sC.

HAKKA IN HISTORY

GRAMMAR 2

INTERROGATIVE 2

The interrogative shenme? what? is placed in the position where the answer is expected. That is to say, after the verb when the question concerns a direct object. Word-for-word: ni yao shenme? [you / want / what?].

2 TYPES OF VERBS

There are two sorts of verb in Chinese: action verbs: like”to go”, “to run”, “to talk”, “to bite” which can be followed bya complement, and adjectival verbs: like “(to be) tired”, “(to be) hungry”, “(to be) good” which are close to adjectives in English but which also contain a verbal element so they are placed directly after the subject, we lei, I am tired.

3. YE – ALSO

Ye, also, always comes before the verb. In a negative sentence, “also” comes before the negative and expresses “not… either” or “neither”. Notice how Chinese economizes on the personal pronoun! Ye bu mai bao? – No, I don’t (want to) buy (a newspaper) either!

4. NA

Na is an exclamation, it expresses well then, then, so …

5. YAO

Yao, to want, can be followed by a noun (to want something) or by a verb (to want to do something). The word order is always: [subject/verb/object].

6. SHENME

Shenme? means what? which?

7. PLURAL OR SINGULAR???

Chinese characters are invariable and therefore have no marker for the plural. It is the context thaT indicates whether a word is singular or plural. but unlike many other languages. in the absence of any precise indication a Chinese word is more likely to be plural: 书 – shu – books; 笔 – bi, pens.

8. SHI

The verb shi, to be, nearly always pronounced with the neutral tone: shi, is usually followed by a noun. Not to be confused in English with “to be” followed by an adjective. In that case, in Chinese shi is not needed because adjectives in such a position, are in fact adjectival verbs, I am tired is wo lei.

9. POSSESSIVE – THE ‘S (APOSTROPHE S)

The possessive (genitive) is often expressed, particularly for kinship ties and personal possessions, simply by placing the word for the “owner” before the “possessed” person or thing: wo fuqin, my father.

10. EXCLAMATIONS!!!!

The adverb jiu – just, is used to insist on or accentuate a certain element in a sentence. ya is used as an exclamation at the end of a sentence: oh! then … ! so there! … , synonymous with the exclamation o!

哦(ò)

| simplified | traditional | pinyin | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 哦 | 哦 | ò | oh (interjection indicating that one has just learned sth) |

就(jiù)

| simplified | traditional | pinyin | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 就 | 就 | jiù | at once; right away; only; just (emphasis); as early as; already; as soon as; then; in that case; as many as; even if; to approach; to move towards; to undertake; to engage in; to suffer; subjected to; to accomplish; to take advantage of; to go with (of foods); with regard to;concerning |

呀(ya)

| simplified | traditional | pinyin | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 呀 | 呀 | ya | (particle equivalent to 啊 after a vowel, expressing surprise or doubt) |

哦! 就 是 他 呀!!

O! jiu shi ta ya!

Oh! So that’s who he is! (oh! then be he then!)

11. PAST PERFECT

The suffix -guo, placed after a verb, indicates that an action has been experienced and is often translated into English with the past perfect.

過(guò)

| traditional | simplified | pinyin | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 過 | 过 | guò | (experienced action marker); to cross; to go over; to pass (time); to celebrate (a holiday); to live; to get along; excessively; too- |

我见过他

Wo jian-quo ta

I’ve seen him before.

是我见过他 Shi, Wo jian-quo ta

Yes, I’ve already met him! (be! I see experiential he)

shi, with the fourth tone accentuated, is used in certain cases to insist on an affirmative answer: yes! or yes, indeed! …In other cases, shl is pronounced with a neutral tone: shi.

12. NO BU WITH YOU

You means to have or there is! are. It is the only verb that does not take the negative bu. The negative, have not or there is! are not, is mei you.

13. THE NEGATIVE YE

ye, also, in a negative sentence, is translated by … either. Adverbs are always placed in front of the verb.

也(yě)

| simplified | traditional | pinyin | definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 也 | 也 | yě | also; too; (in Classical Chinese) final particle implying affirmation |

也没有!

Ye mei you!!

No, there aren’t any either! (Also, negative have!)

GRAMMAR BASICS 1

1. In Chinese, the verb, like all the other parts of speech, is invariable. It has only one written form and one pronunciation. There is no inflexion to indicate the plural or the person; there is no conjugation or tense

2. Suffixes ( 了, le or 过 , guo …) are used to indicate the mode (accomplished, unaccomplished). Adverbs are used to indicate the tense (past, recent past, present, future …).

3. Adverbs always come before the verb. Verbal suffixes (like 过 – go; and 了- le) always come after the verb group.

4. The verb to be, as the copula for introducing a noun, is 是 ~ shi (pronounced in this case with the neutral tone: shi).

这是书 Zhe shi shu This is a book.

他是老师 Ta shi lao shi He is a teacher.

5. The negative for verbs and verbal adjectives is 不 – bu. One exception: the verb to have, 有 – you, which takes 没有 – mei you.

6. 没有 – mei you – is also used to form the negative of the “unaccomplished” action in the past:

我没有去 Wo mei you qu I didn’t go.

他没有吃饭 Ta mei you chi-fan He hasn’t eaten.

不难 Bu nan It’s not difficult.

我不懂 Wo bu dong. I don’t understand.

7. • NEVER use 是 ~ shi in front of a verbal adjective. Verbal adjectives follow the subject directly; although they may be preceded by adverbs:

他很累 Ta hen lei He is very tired.

我不舒服 Wo bu shufu I don’t feel very well.

书不太贵 Shu bu tai gui Books are not too expensive.

8. Subject, verb, object. The subject is generally at the beginning of the sentence, the basic construction being subject/verb/object.

他吃米饭 Ta chi mifan. He eats rice.

我不买书 Wo bu mai shu I don’t buy books.

9. The interrogative particle 吗 – ma is always placed at the end of the sentence.

你去吗? Ni chu ma? Are you going?.

他来过吗? Ta lai-guo ma? Did he already come here??

好吃吗? Hao-chi ma?? Is it good (to eat)?

10. • To ask a question, it is also possible to use the alternative construction: verb/negative/verb:

你去不去? Ni qu-bu-qu?? Are you going???

他来不来? Ta lai-bu-lai? Is he coming??

好吃不好吃? Hao-chi bu hao-chi??? Is it good (to eat)??

你们累不累?? Nimen lei-bu-lei??? Are you tired??

CHINESE CHARACTER TIPS

THE BASIC 3 TYPES OF CHARACTERS

Traditionally in China, characters are divided into three groups:

1. Pictograms.

These are a representation of the object. As such they are similar to hieroglyphs. At the outset, the character for horse represented a horse. Chinese writing has evolved over the centuries, and today, the character for horse 马, although directly descended from the original drawing, no longer really resembles a horse. However, it is still possible to recognize this animal in the unsimplified character: 馬 . In the same way, the character elephant was originally a drawing of an elephant’s head: 象 . The character for bow represented a bow: 弓 . the character for fishing net represented a net: 网 .

2. Ideograms.

These are more abstract, in that they are the representation of a concept; so to rest is written with the element person, 亻 , and the element tree, 木 (A man under a tree being a perfect image of restfulness!): 休 .

The word crowd is made up of three person elements 众 , the word for peaceful is made up of the element for woman, 女. under the 宀 – hence 安 .

3. Ideophonograms.

These are characters composed of two elements: one gives an approximate idea of the meaning, (this part is the “key” or radical, and the other gives an approximate idea of the pronunciation – the phonetic ).

Every character has a radical. According to the traditional listing in classical Chinese, there are 214 radicals. As a result of simplification of the script, in modem dictionaries, the number varies at around 200.The radical indicates the semantic field of the character. There is a water radical, and one for fire, wood, the hand, the moon, the sun, the foot, the heart, etc. For example, many of the characters for weather conditions have the rain radical: the names of many plants and flowers have the grass radical; most of the words for movements of the hand have the hand radical; vocabulary for feelings and emotions have the heart radical. Different methods of cooking all have the fire radical, etc. ldeophonograms are characters that contain an element that indicates the meaning (or the area of meaning) and a second element that gives the pronunciation, or an idea of the pronunciation.

So the word虫国, cricket, is composed of the insect radical: 虫 ; the other element 国 pronounced guo is the phonetic part. Cricket is indeed pronounced guo.

The word ammonia, 氨, has the gas radical: 气 : and the phonetic element is 安 – an; “ammonia” is pronounced an.

Eel, ,鳝 is composed of the fish radical 鱼 and the element 善 that indicates the pronunciation: shan. Mother, 妈 , has the woman radical 女 , and the element 马 giving the pronunciation (apart from the tone!): ma.

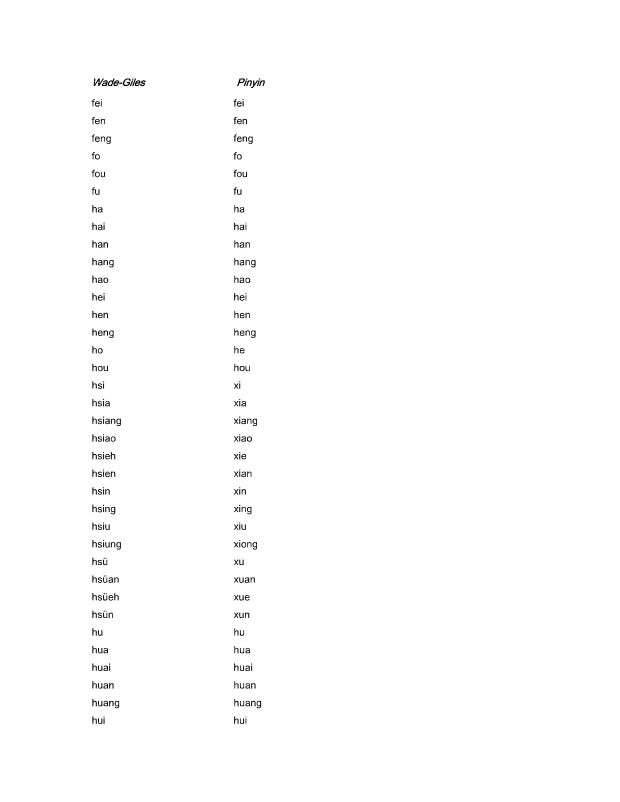

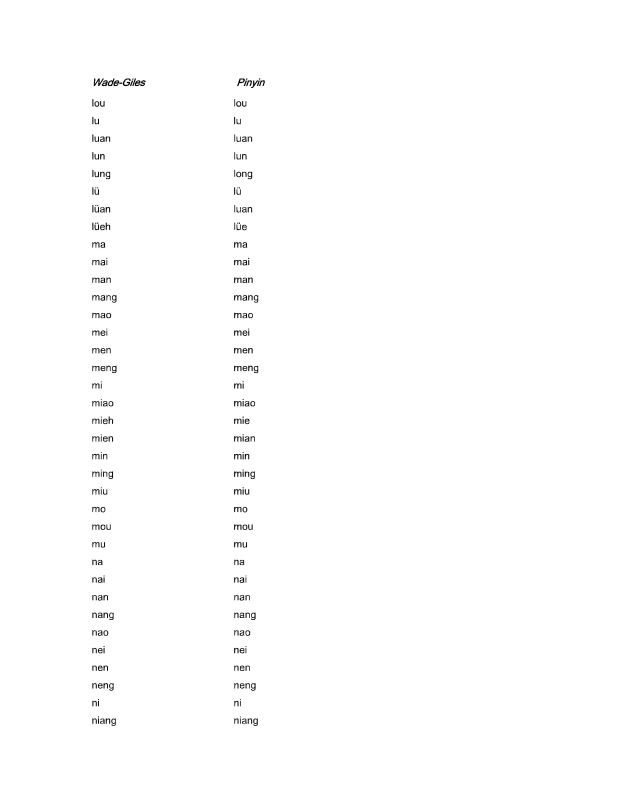

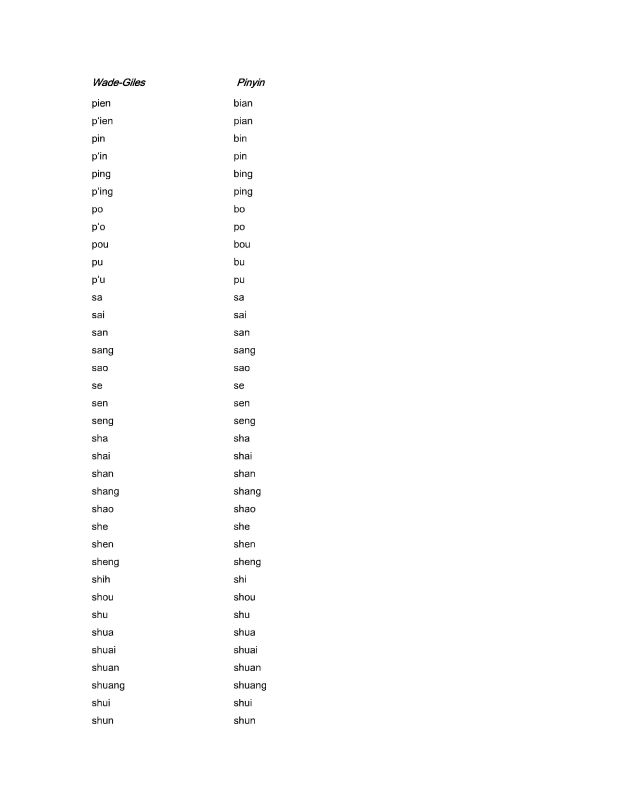

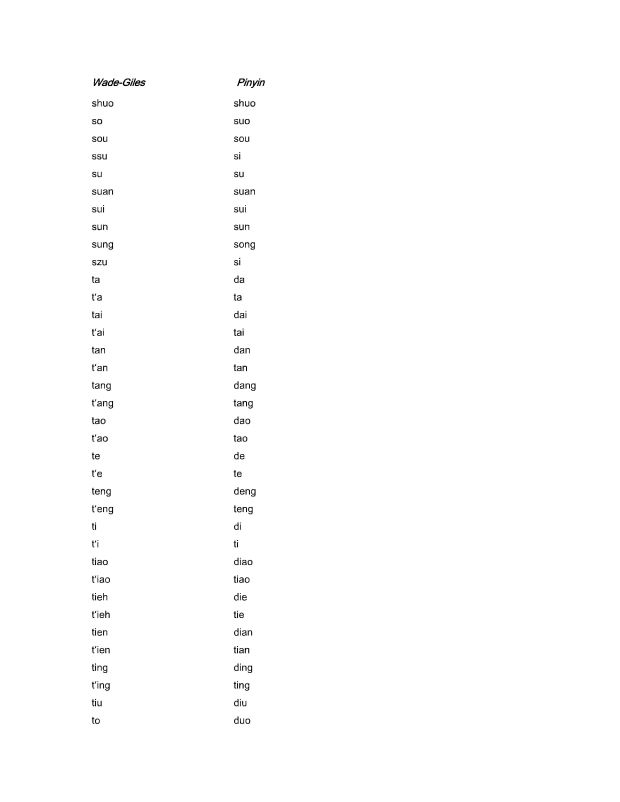

ROMANIZATION 5 – WADE-GILES-PINYIN TABLE

* ALA-LC is a set of standards for romanization, or the representation of text in other writing systems using the Latin alphabet. The initials stand for American Library Association – Library of Congress.

This system is used to represent bibliographic information by North American libraries and the British Library (for acquisitions since 1975),[1] and in publications throughout the English-speaking world.

Correspondence of Wade-Giles to Pinyin

ROMANIZATION 4

* ALA-LC is a set of standards for romanization, or the representation of text in other writing systems using the Latin alphabet. The initials stand for American Library Association – Library of Congress.

This system is used to represent bibliographic information by North American libraries and the British Library (for acquisitions since 1975),[1] and in publications throughout the English-speaking world.

Capitalization

1. Capitalize the first word of a proper noun.

2. Capitalize the first word of a corporate name. Capitalize the first word of the name of a corporate subdivision appearing in conjunction with the name of the larger body only when the subdivision is used in headings.

3. Capitalize each separately written word of a geographical name. Capitalize the first word of the names of a dynasty.

4. Capitalize the first word of the title of a book, periodical, or series.

Punctuation

1. Transcribe a centered point ( • ) indicating coordinate words as a comma. Represent a centered point indicating a space by a space.

索尔 • 呗娄 Suoer Bailou

理查 • M • 尼克逊 Licha M Nikexun

理想 • 劳动 • 幸福 li xiang, lao dong, xing fu

2. Transcribe brackets (「 … 」) or angle brackets (《 … 》) used in the manner of quotation marks (“ … ”) as quotation marks.

《淇 县 志》编 纂 委 员 会 “Qi Xian zhi” bian zuan wei yuan hui

Dates

1. Romanize non-numerical dates as separated syllables, except for reign periods that are also the names of emperors. For example:

光緒己丑 [1889] Guangxu ji chou [1889]

清光緒 15 年 [1889] Qing Guangxu 15 nian [1889]

嘉靖乙卯 [1555] Jiajing yi mao [1555]

民國 79 [1990] Minguo 79 [1990]

康德 3 [1936] Kangde 3 [1936]

明治 1 [1868] Mingzhi 1 [1868]

一九九八年 [1998] yi jiu jiu ba nian [1998]

一九九零年 [1990] yi jiu jiu ling nian [1990]

ROMANIZATION 3

* ALA-LC is a set of standards for romanization, or the representation of text in other writing systems using the Latin alphabet. The initials stand for American Library Association – Library of Congress.

This system is used to represent bibliographic information by North American libraries and the British Library (for acquisitions since 1975),[1] and in publications throughout the English-speaking world.

3. Join together transliterations of two or more characters comprising the names of racial, linguistic, or tribal groupings of mankind. Join the term zu (for tribe or people) to a name only in proper names of places.

基督徒 Jidu tu

桐城派 Tongcheng pai

毛南族 Maonan zu

美国人 Meiguo ren

客家话 Kejia hua

苗族风情录 Miao zu feng qing lu

But:

德宏傣族景颇族自治州 Dehong Daizu Jingpozu Zizhizhou

4. Add an apostrophe before joined syllables that begin with a vowel in cases of ambiguity. For example:

長安市 Chang’an Shi to distinguish it from Changan Shi

延安市 Yan’an Shi to distinguish it from Yanan Shi

张章昂 Zhang Zhang’ang to distinguish it from

张占钢 Zhang Zhangang

劉正安 Liu Zheng’an to distinguish it from

刘镇干 Liu Zhengan

王健安 Wang Jian’an to distinguish it from

王佳南 Wang Jianan

ROMANIZATION 2

* ALA-LC is a set of standards for romanization, or the representation of text in other writing systems using the Latin alphabet. The initials stand for American Library Association – Library of Congress.

This system is used to represent bibliographic information by North American libraries and the British Library (for acquisitions since 1975),[1] and in publications throughout the English-speaking world.2. Join together (without spaces or hyphens) the syllables associated with multi-character geographic names. Do not join the names of jurisdictions and topographical features to geographic names, but separate them from the proper name by a space.

2. Join together (without spaces or hyphens) the syllables associated with multi-character geographic names. Do not join the names of jurisdictions and topographical features to geographic names, but separate them from the proper name by a space.

中华人民共和国史稿 Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo shi gao

臺灣省立博物館 Taiwan Sheng li bo wu guan

西藏自治区文物管理委员会 Xizang Zizhiqu wen wu guan li wei yuan hui

东北林学院 Dongbei lin xue yuan

扬子江 Yangzi Jiang

广州市 Guangzhou Shi

安徽省 Anghui Sheng

商丘地区 Shangqiu Diqu

鹿港镇 Lugang Zhen

纽约市 Nueyue Shi

甘南藏族自治州 Gannan Zangzu Zizhizhou

翠亨村 Ciuheng Cun

浦棠乡 Putang Xiang

海南岛 Hainan Dao

2A. Names of countries. Connect syllables according to the practice followed by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

中华人民共和国 Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo

朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 Chaoxian Minzhu Zhuyi Renmin Gongheguo

中華民國 Zhonghua Minguo

民国档案与民国史学术讨论会论 Minguo dang an yu Minguo shi xue shu tao lun hui lun

文集 wen ji

俄国戏剧史概要 Eguo xi ju shi gai yao

2B. Generic terms for geographical features are capitalized and separated from the names of the features. The syllables of the name of a jurisdiction or geographic feature that are included within another place name are connected together. These practices are also followed when geographic names appear within corporate names. In case of doubt, separate.

海南岛 Hainan Dao

太平洋 Taiping Yang

长江 Chang Jiang

长江口 Changjiang Ko not Chang Jiang Kuo

长江大饭店 Chang Jiang da fan dian not Changjiang da fan dian

珠江水产研究所 Zhu Jiang shui chan yan jiu suo

汾河 Fen He

汾河水库 Fenhe Shuiku

梵净山 Fanjing San

梵净山自然保护区 Fanjingshan Ziran Baohuqu

黑龙江省 Heilongjiang Sheng

黄土高原 Huangtu Gaoyuan

印度半島 Yindu Bandao

2C. Two-syllable place names, in which the second syllable is a generic term. Separate and capitalize a generic term for the jurisdiction.

吳縣 Wu Xian

祁縣 Qi Xian

2D. Place names consisting of more than two syllables. Separate and capitalize a generic term for the jurisdiction.

安徽省 Anhui Sheng

广州市 Guangzhou Shi

高雄市 Gaoxiong Shi

宝山区 Baoshan Qu

鹿港镇 Lugang Zhen

翠亨村 Cuiheng Cun

商丘地区 Shangqiu Diqu

甘南藏族自治州 Gannan Zangzu Zizhizhou

2E. Obsolete terms for administrative units are romanized in the same manner as the names of contemporary places.

福寧州 Funing Zhou

昌平州 Changping Zhou

錦州府 Jinzhou Fu

安順府 Anshun Fu

2F. Names of non-Chinese jurisdictions are romanized in the same manner as the names of Chinese jurisdictions.

加 州 Jia Zhou

紐約市 Niuyue Shi

亞洲 Ya Zhou

東南亞 Dong nan Ya

2G. Terms for archaeological sites, bridges, and other constructions of geographic extent are capitalized and separated from the names themselves. Individual syllables of multi- syllable generic terms are connected together. Individual syllables of multi-syllable generic terms are connected together, as are the syllables of the names of a jurisdiction or geographic feature that are included within the term.

泸州长江大桥 Luzhou Changjiang Daqiao not Luzhou Chang Jiang Daqiao

黄壁庄水库 Huangbizhuang Shuiku not Huangbi Zhuang Shuiku

京杭运河 Jing Hang Yunhe

2H. Names of buildings and other constructions of less than geographic extent. Syllables are separated and not capitalized, except for proper nouns.

黄鶴楼 Huang he lou

聖果寺 Sheng guo si

2I. Names of continents and regions. Generic terms are separated and capitalized in the names of continents and regions. Distinguish when a term refers to a region, and when it refers to direction or position.

亞洲 Ya Zhou

東南亞 Dong nan Ya

北美洲 Bei Mei Zhou

東北 dong bei (when referring to direction or position)

but

東北 Dongbei (when referring to the particular area formerly known as Manchuria

2J. The syllables of personal names that appear within geographic names are connected together. The generic term for the jurisdiction or geographic feature is separated. This rule is an exception to Section 1E.

张自忠路 Zhangzizhong Lu

左权县 Zhoucuan Xian

鲁迅公园 Luxun Gongyuan